Complexion

(Full MFA Thesis) Polaroids are made up of several microscopic layers that come together to form an image. Complexion investigates the ties between this structure and the way that our skin functions.

Abstract

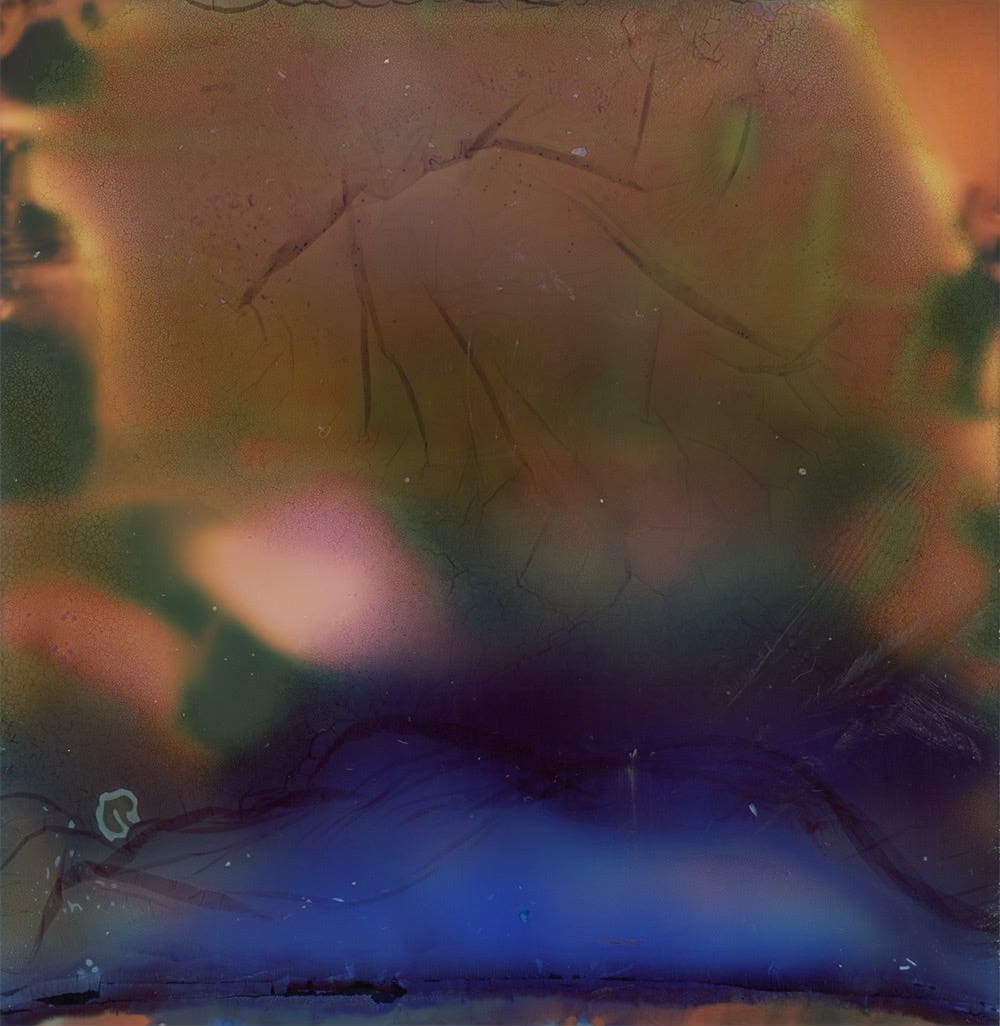

Polaroids are made up of several microscopic layers that come together to form an image. Complexion investigates the ties between this structure and the way that our skin functions. Being diagnosed with eczema as an infant, I have always been hyper-aware of how my emotional stress aggravates my eczema. Complexion depicts how my emotional state alters my skin and warps my experience of reality. Similarly, my imagery undergoes a metamorphosis and influences the chemical changes I create within the Polaroid’s white border. I scan at a high resolution, crop, and reprint the Polaroids at a larger scale. The high-quality scanning highlights the colonies of geometric patterns that spread like capillaries inside the image's space, as well as the bubbles and veils that form inside the Polaroid’s chemistry. The images project into an invisible psychological state of being, showing a reality that we otherwise can't see.

My interest in relating my Polaroids to the skin goes back to my eczema diagnosis when I was four months old. After severe diet changes made almost no improvement, my eczema was linked to emotional stress. My skin is a living roadmap of my emotional space. I experience "flare-ups" when stressed, which causes me to become worried about my eczema, making it flare up more. When the human body experiences stress, whether that stress is emotional or physical, it produces stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. If there is an excess of these hormones, it suppresses the immune system and causes an inflammatory response on the skin.1 The crackling, wrinkled texture and the glistening patches in my imagery are the organ surrounding the image, and metaphorically myself.

I find it fascinating that the body has these involuntary reactions, and how for my skin, this is something that literally comes to the surface. The body's response to stressors is different for everyone, and the ways it can manifest itself seems endless, but these manifestations influence the way we experience reality. A particularly influential exploration of this concept through photography is Don Hertzfeldt’s film It's Such a Beautiful Day.

Hertzfeldt’s film uses the simplified forms of stick figures to tell a story that explores his philosophical understanding of life’s meaning. Stop motion and in-camera effects convey the mental deterioration of the protagonist, the stick figure Bill, as he succumbs to a terminal brain illness that distorts his memory, reality, and identity. He layers the crudely drawn figures with footage he filmed of small glimpses of life, such as the trees on a sidewalk or light filtering through a curtain. He combines them through layering and composite grids of moving imagery. He uses these effects to explore the emotions and experiences associated with terminal illness through simplified stories. This film influences how I think of my work's non-linear structure and layering.2

The ties between our mind and the physical world are what make our reality an individual experience, and when something is wrong with one, it will inevitably influence the other. The way I look at the world emerges from how my emotions and skin respond to their environment. Mental health influences our outlook on life and can cause physical health problems. Growing up miserable in my skin and the convergence of other factors, including genetics, experiences, and brain chemistry, contributed to my early development of depression and social anxiety. While much is still unknown about eczema's relationship to mental health, a recent survey by the National Eczema Association revealed that more than 30% of people with eczema also suffer mental health issues.

A possible explanation for why people with eczema are more susceptible to mental health issues is because of "the way their bodies communicate with their brains during an inflammatory response." A similar feeling links the body's inflammatory reaction to negative emotions; the electrical pulses that our brain creates during an inflammatory reaction are very similar to the signals that the brain creates under emotional distress. This persistent experience of negative feedback in the brain to an automatic response like scratching pave the way for mental health issues down the road.3

For me, something that is a constant physical reminder of how my mental health affects my environment are the dirty dishes in my sink. Part of being depressed is feeling a disconnect from reality. This disconnect drains my energy to do basic household chores, and the dirty dishes in the sink that I have to wash always seem to be a mocking trophy for this weakness I have. This image [Fig. 1] is of my dirty dishes, degraded and turned in on itself, while a dark cloud engulfs them. I need to use the sink, and I need clean dishes, but it means wading through this unknown pool.

There are several layers to a Polaroid image, just as there are to the skin; they can all be distorted and mutilated. Our skin has over ten layers to it; they all work together to create the largest organ in the human body. The skin regulates temperature and protects us from infections and the elements. When there is something wrong with the skin, these layers don't communicate correctly; they fail to produce the right oils and chemicals to keep the skin healthy. This communication failure can result in pain, tenderness, sores, or other complications that are impossible to ignore for whoever lives in that skin.4 Polaroid images have a conceptual relationship to skin. They’re made up of many unseen layers that create the final form we see and are a surface that develops in front of our eyes, as does my eczema.5

A common link in my process is to emulate the blooming rash and disruptive qualities that I experience. In the image above, the emulsion has been dissolved by Isopropyl Alcohol and injected with dye. At the time, I was suffering a horrible flare up that left me in constant pain, and I sought to emulate the disruptive quality that I was feeling in life within a Polaroid. The ink seems to both spread and seep into my skin, and part of the actual rash can be seen on the areas of my skin that are not obscured by the distortion. To manipulate the Polaroids, I alter them physically and chemically. Some of the Polaroids are folded and scraped, while others are injected with alcohol and dyes to break down and mutate the Polaroid's emulsion.

A syringe is a frequent tool I use to alter my images—taking something used for medical purposes and using it on Polaroids ties them further to the human body. The artist's hand is present in the final image, and the artist's hand is what makes the interference between the viewer and the subjects in the Polaroids. When they function correctly, they make an image—disrupting the image development by crushing, stressing, and pushing it to its limits changes the appearance. The delicate layers are disturbed, and the colors begin to mix and bleed together. Working with my hands has always been an extension of how my scratching dictates my skin's health. Sometimes trying to resist the urge to scratch overpowers my brain so much that my nails dig into my skin, trying to focus on something else. Like cells growing back when the body heals, abstraction births new ways for photographs to communicate with us.

There is a back and forth of emotion and physical deterioration of the emulsion. The subject matter and the crackling, swirling pools are layered together, forming new spatial awareness by challenging the eye's focus. Sometimes it's the image, and at other times it's thechipped, toothy feelings that burst out of some photos or the altered color that pops up like a rash on the Polaroid's skin. The emulsion inside serves as its own "self-contained darkroom;" the entire development process happens within the white borders.6 Every image has unique chemical qualities that cannot be reproduced in subsequent exposures, even if the camera is on a tripod.

I take the Polaroids and scan them, crop the white border, and reprint them with an inkjet printer on a larger scale. The high-quality scanning enhances the bubbles and veils that form inside the image's space and highlights the colonies of geometric patterns that spread like capillaries. The disrupted chemistry combined with the act of taking a photograph as the primary motivation of capturing an image–as opposed to the final product being a memorial to a lost moment or experience–sets Polaroids in a different field of understanding as opposed to how we perceive much of photography today.

Polaroids have enticed artists for many reasons, and while some played with scale and layering, like Andy Warhol and David Hockney, there are others who saw Polaroids as a springboard for experimentation and embracing the unknown. Lucas Samaras’s body of work Photo-Transformation is a critical influence on my work. There is a surreal and confrontational energy in Samaras’s close-up Polaroids that substantiates the work in the body as much as it distends into emotional states.

In his Polaroids, he would smear and scratch the wet emulsion of developing Polaroids, mostly self-portraits, to create psychedelic and surreal images. Samaras thought that photography was about the thrill of the camera itself. It was up to him to put the camera somewhere and pose. The confusing and mind-bending feeling in his work comes from manipulating the wet-dye emulsions with a stylus or fingertip before the chemicals set. Noticing the similarities between his Polaroid process and my own encouraged me to look deeper into the artist himself and his personal life. Like me, Samaras made his Polaroids in a New York apartment that also served as his studio. His Polaroids gesture toward a more complicated and reflexive investigation of the self. Samaras photographed his body and face constantly with equal parts anger and self-adoration. His investigation into the constant churning of the self is warped and seems to collapse into abstraction under the weight of reality. His works act as an extension of his body and identity; he twists and blurs his body and reshapes himself in his Polaroids. The sheer number of Samaras’s Polaroids evokes feelings of metamorphosis and flux as opposed to the memory of any specific image.7 Photo-Transformation reassured me that I am not alone in the allure I feel to take a representation of reality and deconstruct it.

Another artist who who worked with the malleability of the Polaroid is Russian artist Galina Kurlat. Her body of work Soft Body embraces the imperfections that are inherent to antiquated photographic processes, transforming traditional portrait photography from the representational to the ephemeral. Kurlat creates a visual relationship between herself and her subject by embracing the possibilities offered by the imperfections inherent to antiquated photographic processes. Chemistry, dust, and the passage of time mark and change the film. Much like flesh, the image continues to change. Recognizable features fade, gestures disappear, obscuring the subject’s identity. The image’s chemistry serves as a veil, forcing the viewer to look through and to look deeper. The potential for a portrait is the final image. The subject of the portrait is poised and ready, but due to the nature of expired film the image never appears. All that’s left is the trace of the Polaroid’s chemistry.

My imagery undergoes a metamorphosis as a result of the physical and chemical changes occurring inside the Polaroid's white boundary. Polaroids transform from a static picture to an ever-changing, vanishing reality. The skin of the Polaroid symbolizes my psychological state, is depicted by the crackling, wrinkled texture and glistening patches. Each picture connects to the next without a clear conceptual division, only a flow from one reality to the next. The images come together to weave emotion and reality into a distorted tangle of deconstructed representation. The artist's hand and the Polaroid's distinctive qualities become variants of the core feeling of a hidden world and feelings that are continually evolving.

This is a full copy with citations of my MFA Thesis, published in 2021. It is available through ProQuest, and here for free. Knowledge shouldn’t die behind paywalls.

ProQuest Number: 28868169

Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author.